Many people argue that democracy is incompatible with capitalism but they differ on whether democracy will kill capitalism or whether capitalism will kill democracy. Peter Thiel, for example, famously said, “I no longer believe that freedom and democracy are compatible.” Thiel’s argument has a long-pedigree. The classical economists from Adam Smith to John Stuart Mill all worried that democracy would kill capitalism. Even Marx and Engels agreed with the analysis arguing that under democracy “The proletariat will use its political supremacy to wrest, by degree, all capital from the bourgeoisie, to centralize all instruments of production in the hands of the State…” they differed only in welcoming such a revolution.

On the other side of the aisle we have the moderns such as Robert Reich and Joseph Stiglitz who argue in Reich’s words that Capitalism is Killing Democracy as “Corporations” and “billionaire capitalists have invested ever greater sums in lobbying, public relations, and even bribes and kickbacks, seeking laws that give them a competitive advantage over their rivals…”

A third argument, consistent with the views of Hayek, Mises, Friedman and others, is that capitalism and democracy are compatible and even mutually reinforcing. Ludwig von Mises, for example, argued that “Liberalism must necessarily demand democracy as its political corollary.”

My latest paper (WP version) (with Vincent Geloso) is in the new book, Can Democracy and Capitalism be Reconciled? We take the third view and show empirically that capitalism and democracy go hand in hand. We also provide some mechanisms for this correlation which I may discuss in a future post.

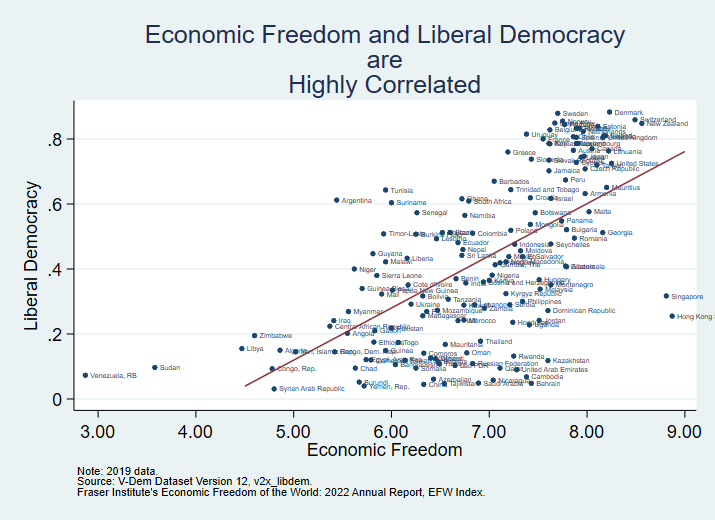

The data is very clear that democracy and capitalism go hand in hand. The figure below, for example, uses the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom Index to measure capitalism and the Varieties of Democracy Index to measure democracy (we use liberal democracy for convenience but show the correlations are strong with any variety of democracy).

Every major democracy is a capitalist country and virtually every capitalist country is a democracy (Singapore and Hong Kong being the only two exceptions.) Moreover, the upper left region–countries with a lot of democracy and low economic freedom, i.e. state control of the economy–what we might call the “Democratic Socialism” region–is empty.

We show further in the paper that changes in democracy are positively correlated with changes in economic freedom. We can see this very clearly by examining a natural experiment–the fall of the Berlin Wall. The fall of the Berlin Wall created a big positive shock to democracy which was followed by large and sustained increases in economic freedom.

It is sometimes argued that only an authoritarian regime is capable of “imposing” big increases in economic freedom and this is clearly false but it is true that there have been large increases in economic freedom in some authoritarian regimes. In the paper we look at the biggest such cases, Peru, Nicaragua, Uganda and Chile. The case of Peru carries some general lessons.

Peru began in 1970 with an authoritarian regime and only modest economic freedom. Economic freedom declined under an authoritarian regime and to levels well below those of any democracy. Modest increases in democracy brought modest increases in economic freedom. Under the authoritarian Fujimori regime there were large increases in economic freedom which in the 2000s were ratified, solidified and strengthened under democratic governments.

What we learn from this brief history is that authoritarian regimes can decrease as well as increase economic freedom. Indeed, one reason we sometimes see big increases in economic freedom under authoritarian regimes is simply that they are starting from the wreckage left by the previous regime. It’s easy to increase economic freedom a lot when you begin with a base level far below that of any democratic regime. Moreover, the Peru case is representative in that when a democratic regime is established it typically does not reject but instead ratifies and strengthens economic freedom.

What accounts for the correlation in economic freedom and democracy? The paper discusses a number of mechanisms of which I will only mention two here. Consider two ways to get rich, redistribution and growth. Redistribution can make a minority rich at the expense of a majority. A dictator can live in luxury amid national misery. But no redistribution scheme can enrich the majority—only growth can. Broad prosperity comes not from dividing wealth, but from creating it through pro-growth, capitalist policies. As a result, in a democracy, the rulers, the demos, can only get rich through growth and this provides some incentive to think about capitalism and economic freedom. The incentive is not a guarantee, of course, democratic voters can vote for bad policies but if they want to get rich they have to think about growth and that means capitalism.

The second reason for the correlation is a negative one, democratic socialism collapses into authoritarian socialism. As Robert Dahl argued:

It is not the inefficiencies of a centrally planned economy…that are most injurious to democratic prospects. It is the economy’s social and political consequences.

A centrally planned economy puts the resources of the entire economy at the disposal of government leaders. …“power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”

A centrally planned economy issues an outright invitation to government leaders, written in bold letters: You are free to use all these economic resources to consolidate and maintain your power!

The bottom line is if you care about economic freedom, democracy is the way to go and if you care about democracy, economic freedom is the way to go.

Read the paper (WP version) for more.

The post Democracy and Capitalism are Mutually Reinforcing appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.