If you’re going to challenge a scientific consensus, you better know the material. Most of us, most of the time, don’t—so deferring to expert consensus is usually the rational strategy. Pushing against the consensus is fine; it’s often how progress happens. But doing it responsibly requires expertise. Yet in my experience the loudest anti-consensus voices—on vaccines, climate, macroeconomics, whatever—tend to be the least informed.

This isn’t just my anecdotal impression. A paper by Light, Fernbach, Geana, and Sloman shows that opposition to the consensus is positively correlated with knowledge overconfidence. Now you may wonder. Isn’t this circular? If someone claims the consensus view is wrong we can’t just say that proves they don’t know what they are talking about. Indeed. Thus Light, Fernbach, Geana and Sloman do something clever. They ask respondents a series of questions on uncontroversial scientific topics. Questions such as:

1. True or false? The center of the earth is very hot: True

2. True or false? The continents have been moving their location for millions of years and will continue to move. True

3. True or false? The oxygen we breathe comes from plants: True

4. True or false? Antibiotics kills viruses as well as bacteria: False

5. True or false? All insects have eight legs: False

6. True or false? All radioactivity is man made: False

7. True or false? Men and women normally have the same number of chromosomes: True

8. True or false? Lasers work by focusing sound waves: False

9. True or false? Almost all food energy for living organisms comes originally from sunlight: True

10. True or false? Electrons are smaller than atoms: True

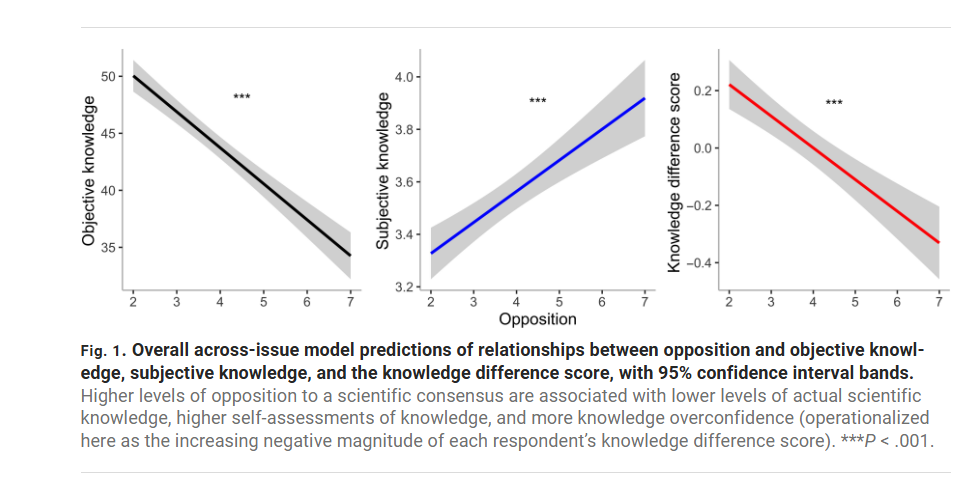

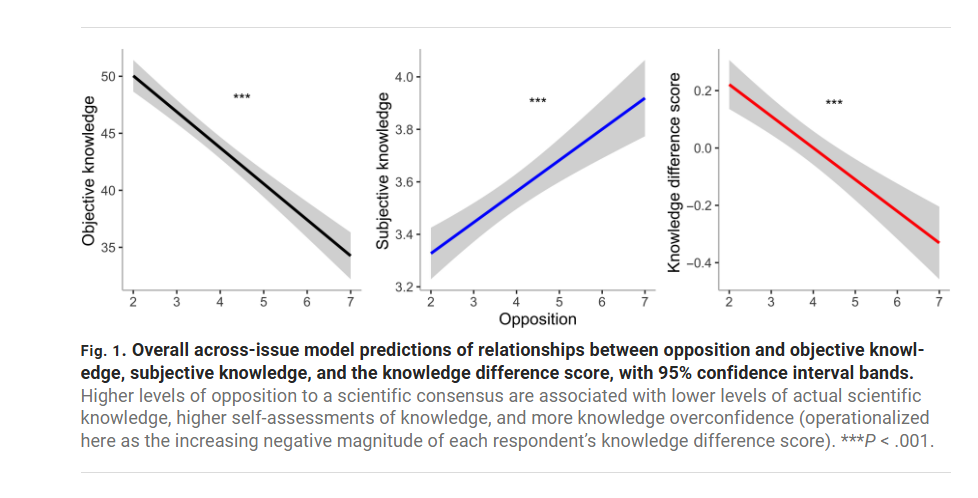

The authors then correlate respondents’ scores on the objective (uncontroversial) knowledge with their opposition to the scientific consensus on topics like vaccination, nuclear power, and homeopathy. The result is striking: people who are most opposed to the consensus (7, the far right of the horizontal axis in the figure below) score lower on objective knowledge but express higher subjective confidence. In other words, anti-consensus respondents are the most confidently wrong—the gap between what they know and what they think they know is widest.

In a nice test the authors show that the confidently wrong are not just braggadocios they actually believe they know because they are more willing to bet on the objective knowledge questions and, of course, they lose their shirts. A bet is a tax on bullshit.

The implications matter. The “knowledge deficit” approach (just give people more fact) breaks down when the least-informed are also the most certain they’re experts. The authors suggest leaning on social norms and respected community figures instead. My own experience points to the role of context: in a classroom, the direction of information flow is clearer, and confidently wrong pushback is rarer than on Twitter or the blog. I welcome questions in class—they’re usually great—but they work best when there’s at least a shared premise that the point is to learn.

Hat tip: Cremieux

The post Confidently Wrong appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.