By the time she arrived in the United Kingdom from Chile in March 2024, Pía Loren had already been to conferences in Latin America and Europe. Attending another international conference was a condition of her grant.

The 25th Global Nephrology, Urology and Kidney Failure Congress caught her eye, because the conference website listed several “renowned speakers”.

But on arriving at the conference venue, a four-star hotel near London’s Heathrow airport, Loren could find no conference signage. Eventually she knocked on a door with a sign reading ‘Pulsus meeting’, a name Loren didn’t recognize. Inside, a flustered young man told her that the nephrology congress was being held in conjunction with other medical events.

Inside were three rows of desks, which would be occupied by a total of 21 people over the course of the day. The first two in-person talks were about ophthalmology. Subsequent talks covered drug toxicity, dentistry and antibiotics. Loren and the other attendees became increasingly flummoxed as the day went on. One had come from Jamaica for a midwifery conference, but no midwifery talk was delivered. Others had travelled from countries including Ukraine, Iran and the United States. The conference company had also scheduled a renewable-energy conference for the same date and venue. These had all morphed into what the organizer, named Conference Series, called the 30th Global Healthcare Summit. Conference Series, like Pulsus, is part of a publisher and conference organizer named OMICS International.

How I overcame my stage fright in the lab

A Nature reporter attended the event, and found it to be shambolic. It was facilitated by a PhD student, who said that she had been asked by e-mail just a couple of days beforehand to take on the extra, unpaid role of delivering a conference speech. The conference administrator, who said that a friend had told him a few days earlier of the paid, one-off gig, had brought his laptop, but attendees had to run back to their hotel rooms to gather the connecting cables needed for presentations. No one from Conference Series was present.

The nine sessions were swapped around in a dizzying way. And although the conference was due to run until 5.30 p.m., it was abruptly wrapped up at 12.30 p.m., to general confusion. People who were supposed to give poster presentations — including one who had shepherded hers on two flights — left with their posters still wrapped.

Loren, a postdoctoral researcher in molecular biology at Chile’s University of the Frontier, based in Temuco, realized then that she had travelled to London for no real reason. She was told that the second day of the conference would be held online, and she would give her talk (along with other nephrology talks) virtually. So, she delivered her talk to a handful of people on Zoom from a friend’s house, outside London, where she was staying.

Like the in-person event, the online programme was chaotic. The meeting’s host disappeared for stretches; at one point, Nature’s reporter was made the host. One speaker presented four times. Besides Loren’s, not a single presentation related to nephrology.

Nature contacted OMICS to ask about the conference, but did not hear back.

Overall, it was “a super-depressing experience”, Loren says. “I never thought that, in a developed country like the UK, this situation would happen to me.”

What is a predatory conference?

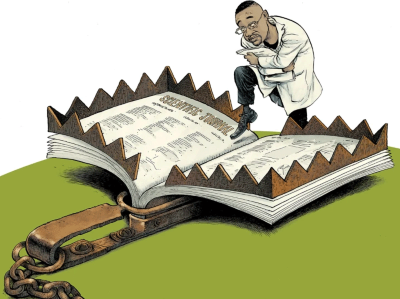

Nature attended the in-person and the virtual event alongside Loren as part of an investigation into predatory conferences. These are in some ways similar to predatory journals, which promise to publish research of any kind without proper peer review — for a fee. And, like predatory journals, predatory conferences can be hard to define. Criteria often listed include weak or no peer review for presentations, poor organization and a focus on making the organizers money.

Vicki Mayer travelled from Louisiana to London for an event that was mysteriously postponed.Credit: Arielle Pentes

James McCrostie, who researches business administration at Daito Bunka University in Tokyo, thinks that the number of predatory conferences is continuing to grow, and that organizers are swift to change their practices to evade detection. He also thinks that ‘vulture conferences’, to use a Japanese term, are now more plentiful than legitimate ones.

The InterAcademy Partnership (IAP), an international network of more than 140 science academies, has detailed a spectrum of conference types. At one end is outright deceit and fraud — such as when conference websites list speakers who have never heard of the meeting, when organizers collect registration fees for a conference that never takes place, or when they promise peer review that doesn’t materialize. At the other are best practices — including a well-defined scientific purpose, affiliation with reputable organizations and thorough peer review. A range of activities exists in between, including some of questionable or low quality. The IAP suggests that predatory conferences are especially rife in medicine and dentistry.

Why do people attend problematic conferences?

“Predatory conferences often remain under the radar,” says Tereza Šímová, an open-science advocate at OpenAIRE, a non-profit organization based in Athens, and at the Czech Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Philosophy in Prague. A key reason that they persist, she says, is that “researchers, especially those eager to strengthen their publication records, are sometimes lured by the promise of subsequent publication indexed in reputable citation databases”, such as in conference proceedings or in journals published by the conference organizer.

The COVID-19 pandemic, online conferences and social media have created further opportunities for predation, says Diane Negra, who co-chairs the IAP and researches film studies and screen culture at University College Dublin. Researchers have come to expect some level of disorder in virtual interactions, as well as turnover among academic staff — so they might not notice when they’re falling prey to a low-impact conference. “New norms of brusqueness and inaccessibility mean that potential attendees may find it hard to reach human organizers or to obtain clear information,” Negra says.

Jeffrey Beall, a former academic librarian who famously created a list of predatory journals, says young researchers with limited conference experience, and those attending an event that isn’t in their first language, are especially at risk. “It’s easy for people to be fooled.”

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

Established academics can also be vulnerable to predatory conferences when they seek to develop expertise in a new research area. In 2017, Vicki Mayer, a communications researcher at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, was interested in the internal dynamics of the data-centre industry, something that few people were investigating at the time.

A colleague told her about a conference organization that ran relevant professional events, one of which was to be held in London. Travel costs were at least US$1,000, Mayer says, but the trip seemed worthwhile. Yet when she arrived at the venue, there were no signs for the conference. “I just remember the feeling of my heart starting to pound, like ‘Oh my God, there’s nothing here. What am I doing here?’” The conference website was no longer online, either.

After some frantic e-mails and phone calls, Mayer was told that the conference had been postponed, and a refund was issued. All in all, “it was just very upsetting”. She found it especially ludicrous that “I went through all this trouble to get my money back”, and a month later the same company invited her to be a speaker. The experience has transformed her approach to conferences: she now attends fewer meetings, and does more research on the organizers beforehand.

Supply and demand

Unlike Mayer, some researchers might register for dubious conferences for other, strategic reasons. They might be flattered to be invited or attracted by a glamorous location; questionable conferences often take place in tourist hotspots. Or they might attend simply to add a line to their CV.

McCrostie sees it as a case of supply and demand. “The problem is there’s not enough speaking spaces at these legitimate conferences, so scholars that need to present … and can’t get in at the famous conference will go to the predatory conference.”

“When I started my research, I assumed that most academics were unwittingly attending,” McCrostie explains. “Unfortunately, after encountering so many academics willingly supporting the companies, I must conclude that most, but certainly not all, either know the conference has no value or they want to pretend to themselves they don’t know.”

How restorative justice could help to heal science communities torn apart by harassment misconduct

In an IAP survey of more than 1,800 researchers in 112 countries, published in 2022, 6% didn’t know whether they had taken part in a predatory conference; 3% reported having participated in a predatory conference unwittingly; and 1% had participated despite knowing that the conference was predatory.

But this isn’t simply a harmless way to pad out a CV, McCrostie warns. In general, conferences without quality control can decrease the credibility of presented and published science at those events, he says. They might also have a longer-term negative impact on researchers in the medical field, for whom keeping up to date is crucial to ensuring consistent treatment of patients.

Big business

The company that organized the event attended by Loren and Nature was variously called Conference Series and Pulsus. OMICS, the parent company, was ordered by a US court in 2019 to return more than $50 million made through deceptive business practices in the fields of scientific publishing and conferences. But despite this rare sanction, OMICS continues to operate. Nature contacted OMICS for this article but did not receive a reply.

Observers point out that this type of enterprise can be lucrative. “It’s an easy business model to copy,” Beall says. “All you have to do is have a website and some fancy graphics and you can be in business in a week.” In 2018, journalists Svea Eckert and Peter Hornung ran a sting operation: they wrote a nonsensical paper, giving a made-up university as their affiliation, which they presented at a London conference of the World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology (WASET). With their colleagues, they estimated that WASET earned revenue of nearly $4.5 million for a year of 157 events that each included many separate conferences.

Collection: Life in the lab

Nature contacted WASET, which denied being a predatory organizer, and said it had detailed quality checks in place for its conference proceedings. The spokesperson for WASET also said that its conference proceedings and abstracts are all available online, furthering the cause of open science.

As part of their investigation, Eckert and Hornung also revealed to Robert Huber, a Nobel laureate in chemistry, that a Conference Series meeting he had attended had been ‘fake’. “Seldom are the organizers of fake conferences held accountable,” they concluded in a resulting documentary.

The costs of hosting an academic conference can be modest. A sales representative at the hotel hosting Loren’s conference said that a room for approximately 20 people could be hired for £500 a day, with a further £60 per person for lunch and refreshments. Attendees at Loren’s conference reported paying a varying range of fees. Loren asked for a refund of the $520 registration fee she paid, but had not received this by the time this article went to press.

For a separate Conference Series event that Nature investigated, the cheapest fee of 51 options was €140 ($150) for an e-poster, early-bird registration. The most expensive, which involved exhibiting and final registration, was €1,783.

Nature contacted OMICS and Conference Series for comment about their fee structure, but did not receive a reply.

A junior doctor at a prestigious London hospital was especially troubled. Her name and signature appeared on the certificates of attendance handed out to the other attendees, without her approval, at the event that Loren attended in March: it seemed to the doctor that the organizers were using her institute’s renown to add a sheen of respectability to the conference. She was later accused by an angry attendee of being part of the fraud; the accusation left her shaking.

Attendees of this Global Healthcare Summit described being embarrassed, confused or angry. But they weren’t sure whether they would tell others about their experiences. Some said that they wouldn’t mention anything about the conference, for fear of damaging their own reputation; others admitted that they could still use the conference to beef up their CVs and accumulate points for continuing professional development.

Loren was unusual in being comfortable with speaking out. “I had never attended one as unworthy as the global healthcare conference,” Loren says now. “I hope that all the people involved are brought down as soon as possible.”