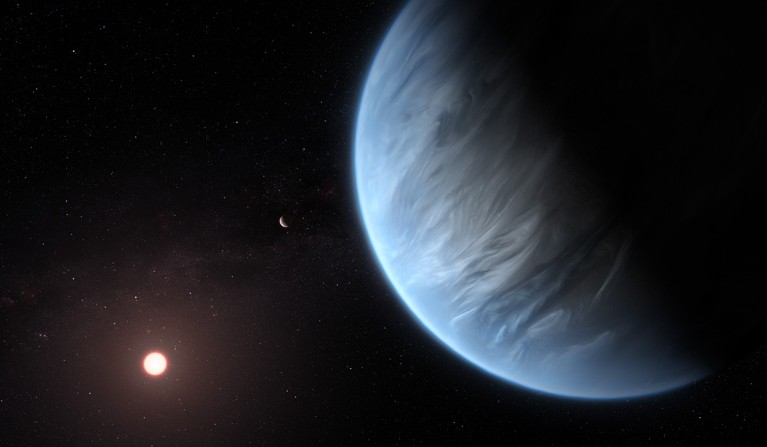

An artist’s impression of K2-18 b, where researchers report a signature of life’s activity.Credit: ESA/Hubble, M. Kornmesser

A University of Cambridge-led team of astronomers made worldwide headlines last night with claims that they had found the “strongest hints yet of biological activity outside the Solar System”. The discovery involves a distant planet known as K2-18 b, which the team says has one or more molecules in its atmosphere that might have been generated by living things1.

The announcement has been met with floods of scepticism from other researchers who study such ‘biosignatures’ in exoplanet atmospheres.

“It is not strong evidence,” says Stephen Schmidt, an astronomer at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. “It’s almost certainly not life,” says Tessa Fisher, an astrobiologist at the University of Arizona in Tucson.

Here, Nature explores the high-profile claim — and why many scientists say it’s far from proof of alien life.

What has been found?

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the Cambridge team reported finding hints of the molecule dimethyl sulfide (DMS), a pungent smelling compound that can be produced by bacteria, in the atmosphere of K2-18 b, a planet smaller than Neptune that lies about 38 parsecs from Earth. The scientists detected the molecule by analysing starlight as it filtered through the planet’s atmosphere; different chemical compounds leave identifying imprints in the light’s spectrum. The data might indicate the presence of the related molecule dimethyl disulfide (DMDS), either in addition to DMS or in its stead1. These chemicals are intriguing because on Earth they are produced by living organisms such as marine phytoplankton.

In 2023, the researchers reported similar findings2. This follow-up work looks at the planet in a different set of wavelengths and is a stronger and cleaner signal that the molecules are present, the team says.

Being able to tease out the detailed chemistry of a faraway planet is a technical tour-de-force, the researchers say. “What we are seeing is a major paradigm shift in the field of exoplanet science,” said team leader Nikku Madhusudhan, an astronomer at Cambridge, in a livestreamed colloquium on 17 April. He did not respond to a request for an interview before press time for this story.

Why is it important?

Scientists have been looking for life beyond Earth for centuries. If DMS and DMDS do exist in this planet’s atmosphere, and if they are formed by biological activity, it would represent a groundbreaking moment in the search for extraterrestrial life.

The work also marks a step toward understanding planets like K2-18 b, which are some of the most common of the 5,800-plus planets that have so far been identified throughout the universe. They are referred to as ‘mini Neptunes’ based on their mass, but beyond that, little is known about their makeup. Some researchers, including Madhusudhan’s team, say that some could be exotic water worlds cloaked in hydrogen atmospheres3. If so, they may be some of the best places to look for the existence of extraterrestrial life.

Why are other researchers skeptical?

For starters, there are questions about whether K2-18 b even has water — or a surface where anything could live. Modelling studies of it and similar planets suggest that they are probably barren5,4. “A lifeless mini-Neptune scenario remains the most parsimonious explanation,” says Joshua Krissansen-Totton, a planetary scientist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Then there’s the issue of whether DMS/DMDS is actually present, or whether it is a spurious signal. The measurement reported by the Cambridge team is “really pushing the limit of what JWST can do,” says Laura Kreidberg, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany.

Schmidt and his colleagues recently re-analysed the 2023 claim from the Cambridge team and found no evidence of biosignature molecules in that data6. Schmidt says the new observations are “pretty noisy, and any reported features could still just be statistical fluctuations”. For their part, the Cambridge researchers say there is just a 0.3% probability that the signal could be due to chance.