Emmanuel Lafont/ Getty Images

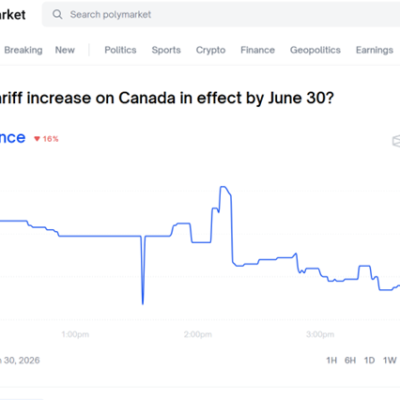

Emmanuel Lafont/ Getty ImagesCelebrating the 30th anniversary of his legendary stage production, Matthew Bourne tells the BBC about the show that radically changed ballet with one “big idea”.

The most iconic dance costume of recent times may be a pair of white feathery breeches on permanent display at London’s V&A museum. They’re a tribute to choreographer Matthew Bourne’s gender-flipping dance version of the ballet Swan Lake. The production, which first premiered in London in November 1995, ruffled feathers in many ways because the swans, until then female roles, were played by male dancers. It went on to become the longest running full-length dance classic in the West End and on Broadway, winning both Olivier and Tony awards.

As the show celebrates its 30th anniversary with a 2024/25 tour, Matthew Bourne tells the BBC the story of the landmark production.

“I think most people thought that when they came to see it, they were going to see men in tutus,” says Matthew Bourne, of public expectations back in 1995.

The young, London-born choreographer, then aged 35, had been given the opportunity to stage his own version of Swan Lake at London’s Sadler’s Wells Theatre. It was a cherished dream for him, he says, “because I’ve always loved and identified with the story”. His big idea, he recalls, “was that all the swans would be male. Everything else about the production flowed from that one simple idea”.

He explains that he found the meaning in the story through the character of the prince. “He’s constantly being told he needs to get married; his mother keeps pointing at the ring on her finger, which is ballet mime for ‘time to get married’. And he keeps saying, ‘no I’ll only get married for true love’. I always thought there was something else going on there. And that’s where the idea of male swans came from, from thinking about the prince himself. I think he’s obviously looking for something else.”

Bourne trained in dance before becoming a choreographer for television and theatre, and by the early 1990s, had form for putting his own spin on classical ballets. Like the cohort during that era known as the YBAs (Young British Artists) – which included Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas – Bourne was seen as an agent of change in his sphere. He had critical success with his version of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, where the setting was a Victorian-style orphanage. In 1994, his version of La Sylphide (called Highland Fling) was set in a modern-day housing estate in Glasgow.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUntil this audacious twist on Swan Lake, ballerina Margot Fonteyn’s legendary performances as the Dying Swan had become an iconic image not just of Swan Lake, but of 20th-Century ballet itself. When it was announced that Bourne was bringing his own version, he remembers that “a lot of people thought it was a folly”.

“No one could really imagine what it would be like, I think,” he says. “If you’d been asked what ballet looks like, I think the image of female swans, the dancers, the tutus, was the classical look anyone would imagine.”

“They said things like ‘he’s not the right person to do a new version of Swan Lake, he’s known for humour and a jokey approach to things, for parody.’ I was called ‘the bad boy of the ballet’ – I’m not even from the ballet world – and ‘the Damien Hirst of Dance’. They thought it was going to be a big send up and there were a lot of people who were either doubting it, or excited that this funny piece was going to happen.

“But I knew I wasn’t going to do that. I knew I had a good idea. Whether people would like it or not, that I didn’t know.”

Matthew Bourne’s Five Culture Shifters

A Chorus Line by Marvin Hamlisch and Edward Kleban (1975)

Essentially an experimental workshop production about a group of dancers auditioning for a traditional Broadway show but along the way it has profound things to say about life, love, acceptance and everything in-between. The secret of its success? It is about all of us.

The Kick Inside by Kate Bush (1978) (and everything since!)

Unique then and unique now! Spellbinding music from an artist who has always danced to her own tune. Accept no imitations!

The Homecoming by Harold Pinter (1965)

A riveting play that still has the power to shock 60 years on. Complex and simple at the same time, Pinter’s world is a place where there are lots of questions posed and no easy answers – it’s a challenging world that I love delving into.

Maurice by EM Forster (published posthumously 1971)

The first gay romance novel… and it has a happy ending! (Also a superb Merchant Ivory film).

A vision of the future! Mind-blowing technology coupled with a surprisingly moving and classy spectacle celebrating the joyous alchemy that is Abba.

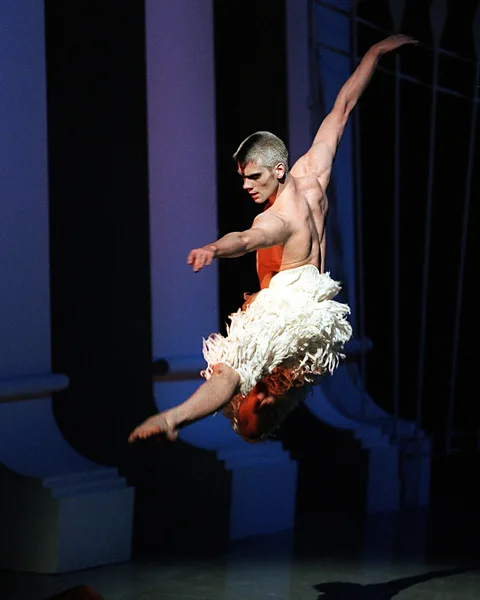

Part of the visual surprise of the show were the male swans. The look – a single black triangle on their foreheads, cropped hair, bare torsos and feet, and most famously, their white silk chiffon “feathered” legs – were created by Bourne and British designer Lez Brotherston. Bourne was also influenced by Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film, The Birds.

“Lez and I wanted the swans to have a sense of being bird-like, animalistic and human, all at the same time,” he says. “That they’re mythical and tribal as a group. I had a few visual images, that I gave to Lez, of an Indian dancer that I’d seen jumping in the air with some fringy trousers. He also came up with a beautiful, slightly corseted, top half. For the ‘beak’ make-up, I’d seen a ballet by Roland Petit, Notre Dame de Paris. The only make-up he had to represent the hunchback was a black square line across his eyebrows. I’d just remembered how simple it was and how it worked well.”

Far from being a humorous version of the original love story, Bourne describes his Prince’s connection with The Swan as “the heart of the piece for me”.

“This Prince is looking for something in his life that he didn’t have,” he says. “He has a cold mother, no one touches him, which is true of a royal person if you think about it. So, to be embraced by the swan’s wings was the heart of it. It represented to him all the things that he wasn’t in his own life, which is being free and being wild, to be a free person. It’s so well embraced by Tchaikovsky’s music. It’s very moving, deep stuff, because the story has an element where you can bring yourself to it.”

The choreographer also expresses surprise – as the costumes for his ‘royal’ family were contemporary – that the 1995 headlines mainly focused on The Swan, rather than a perceived connection with the British Royal Family and the divorce of the then Prince of Wales from Diana, Princess of Wales.

“The royal news was so big at the time and the lead did look a bit like Prince Charles at one point. So, I thought that would be picked up on, the story of a troubled prince. But it was all about the cultural icon, which is the Dancing Swan.”

Gliding into pop culture

The world premiere of Swan Lake, on 9 November 1995, with Adam Cooper, a Royal Ballet principal dancer playing The Swan, caused an immediate sensation.

“It was a shock to many in the audience, I think, when Adam Cooper and these men in costumes came on,” Bourne says.

“It wasn’t a bad shock; it was just something brand new. And it was a shock to me, the way it took off in one night. We were front-page headlines in some newspapers. Cameron Mackintosh cornered me in the interval – he didn’t even wait for the end of the show – and said that it had to go to the West End. He recognised something in it immediately.”

There were, he adds, some who walked out when two men started dancing together, and the sexuality of the piece was a talking point throughout its first record-breaking runs in London’s West End in 1996, and on Broadway in 1998. It was still a controversial topic. Although same-sex marriage had been depicted in the US’s most popular sitcom, Friends, in January 1996, weeks after the premiere of Swan Lake, it would still be another two decades before gay relationships would achieve full equality in law in either the US or Great Britain.

Getty Images

Getty Images“It got labelled ‘the Gay Swan Lake’ in a lot of places, and I was told to keep quiet about it when we first went to Broadway,” Bourne says. “They thought it was very bad for publicity. It wouldn’t be now, of course.”

“Deep down, I knew there was essentially a gay story being told within the piece,” he says. “I think I was wary of going too far with it at the time, and thinking of everyone’s comfort. I’d be saying about The Swan, ‘he is like a father figure’.”

“I think that a wider audience found it more palatable in the mid-1990s because it wasn’t a straightforward gay relationship. It was a prince and a swan. It was seen through the eyes of a prince trying to find peace in his life, and trying to find someone who would love him. It has a simple universal theme, which you could read several ways, and I think its openness is part of its success. But there were people who didn’t like that side of it.”

If Bourne didn’t feel able to celebrate the queer narrative within this Swan Lake in 1995, the rest of the dance world took much longer. It wasn’t until the 2020s that popular TV dance shows featured same-sex couples, and it was only this year that classical ballet premiered a new ballet, Oscar, with an openly gay story.

“Those barriers have just been broken, which is interesting,” says Bourne. “The 30 years of history has changed all of it, it’s not seen as controversial anymore, it’s ‘bring the kids at Christmas, bring the family’. It’s changed enormously. But it’s gone through a history of whether I can openly celebrate that as well, and I’ve gone on my own journey about how I talk about it.”

Swan Lake’s role in helping to question gender norms of that era, however, was evident in Stephen Daldry’s Oscar-nominated film from 2000, Billy Elliot, where Jamie Bell stars as a boy who wants to dance. Adam Cooper stars in the last scene of the film, as adult Billy, about to perform as The Swan.

Alamy

AlamyWith that one scene, Swan Lake glided into pop culture. And Bourne believes the production had a direct influence on the number of young men who now felt able to pursue a career in dance.”Around that time there was an incredible growth in interest from young men, as well as young women, to get into dancing,” he says.

“I think it has a legacy in terms of male dancers, along with Billy Elliot, from that time. It became an okay thing to do, because of these swans, this great combination of masculinity and lyricism, they show that both can be embraced. It’s an iconic piece that they aspire to learn now.”

Swan Lake also broke new barriers when it won a British Olivier theatre award in 1996, and three Tony Awards in 1999, including best director of a musical. It caused consternation among some on Broadway as they were divided on what his production represented. It was almost beyond definition, a contemporary piece set to the original music of Tchaikovsky.

“It is a musical theatre piece, but there was all this controversy about me winning the Tony Award, because there were some who said that Swan Lake wasn’t a musical, it’s a ballet,” says Bourne. “But anything of this nature, this kind of argument, is always interesting because that’s how things change, and how things are then viewed differently.”

But that many audiences do indeed see his Swan Lake (and his subsequent dance productions) as ballet, has had a lasting impact on the inclusivity of the art form, he thinks. “I think the thing I’m most proud of with Swan Lake is the growth of dance audiences because of that piece, it really embraced wider audiences,” he says.

“I think it made people eager for creativity and wanting something different. That’s been a definite legacy of the show. And for some people, what we do is ballet, and they want to appreciate that they’ve found something new, which is, for them, ballet. So, it’s all about definitions really. Perhaps we’re just a genre on our own.”

Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake is on tour from November 2024 for 29 weeks.